Vienna, 14 July 1933

The Struggle for a Fairer World: Antifascist Writer Else Feldmann

Unions’ evening of the Association of Socialist Writers – a report on the lecture by our correspondent Laura Sarochova

© Archive Setzer-Tschiedel / brandstaetter images / picturedesk.com

Yesterday evening, our reporter had the opportunity to meet not only the poet Theodor Kramer and the writer Adele Jelinek, but also the most famous and successful journalist and writer of our time: Else Feldmann!

From Theatre to Journalism

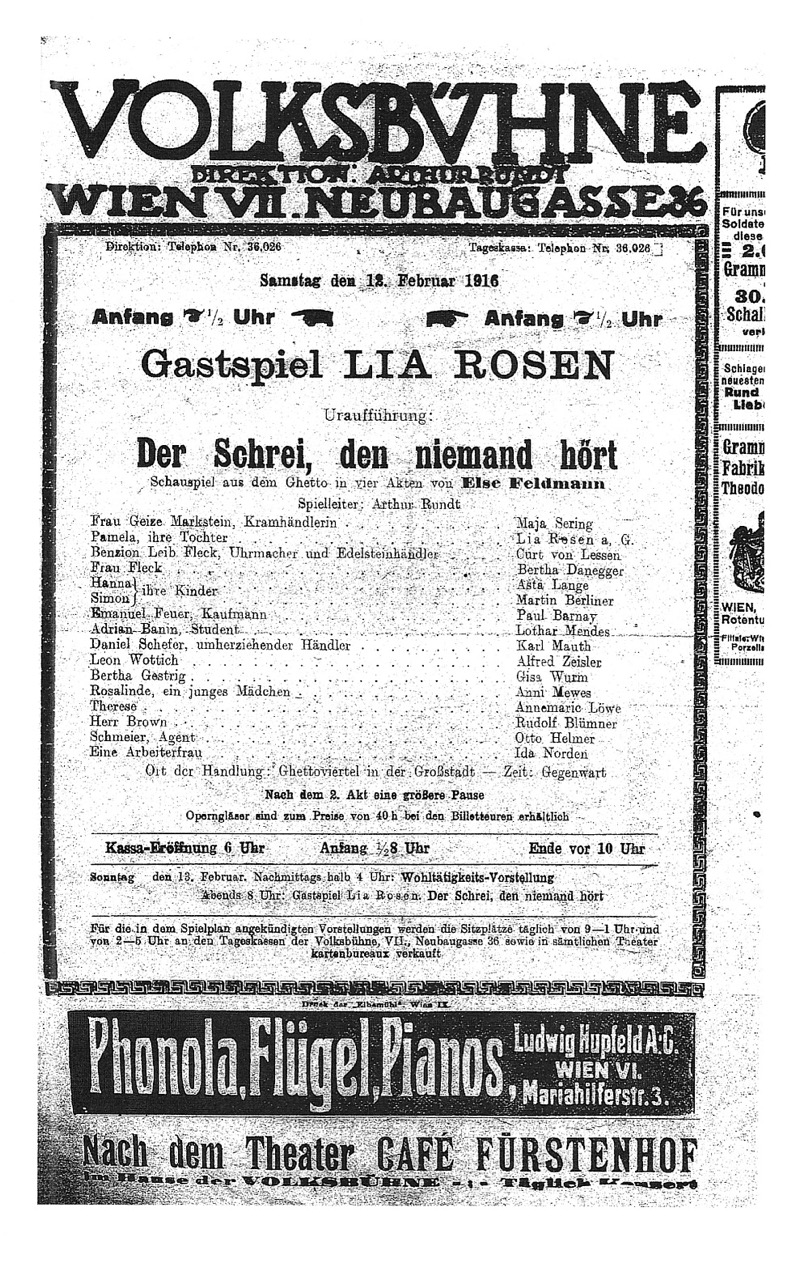

I am currently in the anteroom of the hall of the Union of Stage Workers, where lectures by socialist authors are taking place tonight. Before the event begins, I meet Else Feldmann for a conversation. In today’s volatile political situation, Feldmann’s novels can be found in every bookstore, and the themes of her work are more relevant today than ever. Seventeen years ago, she made her debut as a playwright at the Vienna Volksbühne with the play Der Schrei, den niemand hört. Trauerspiel aus dem Ghetto (‘The Cry That No One Hears: A Tragedy from the Ghetto’). Empathic and knowledgeable, Feldmann presented her social and political views in this play. No other works of hers have yet been performed, but Feldmann tells us that she has begun to work on other dramas. We can therefore look forward to a new premiere of one of Feldmann’s plays. However, the author emphasizes that her publishing and writing activities are of the highest priority with regard to the current political situation.

Social Critique in Every Word

We remember her explosive reports Bilder vom Jugendgericht (‘Images from the Youth Court’) from the years 1917 and 1918. Her commitment to a fairer world and the fight against social injustice characterizes all her work. Thus, her first novel, Löwenzahn. Eine Kindheit (‘Dandelion: A Childhood’) from 1921 offers a glimpse into the lives of women in Vienna's proletarian milieu; a new edition of this novel appeared in 1930 under the title Melodie in Moll (‘Melody in Minor’). Her next novel, Der Leib der Mutter (‘The Mother’s Body’), also focuses on the plight of women. This great work was initially published as a serialized novel in the Arbeiter-Zeitung in 1924 and has now been available in book form for two years now.

g

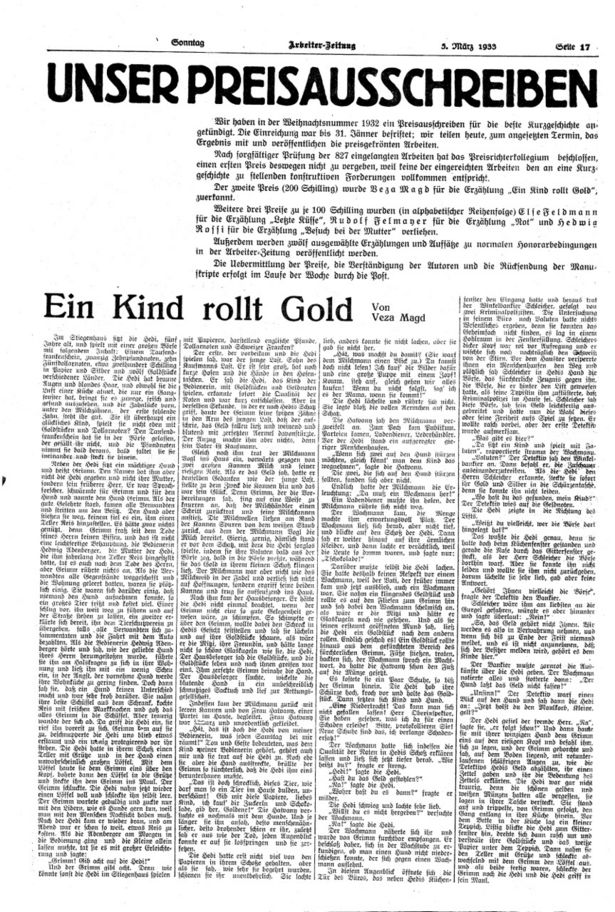

One of her works from the past year, the short story Letzte Küsse (‘Last Kisses’), which won third prize in the Arbeiter-Zeitung competition, also deals with current social issues, such as rampant tuberculosis. She is currently working on a new serial novel that describes the lives of two sisters and their everyday struggles. However, we must not forget her other publishing activities, because in both feature articles and in reviews as well as her short stories, Feldmann continuously devotes herself to the issues of our time and proposes ideas for a new, fairer world.

Associations as Meeting Places for Intellectuals

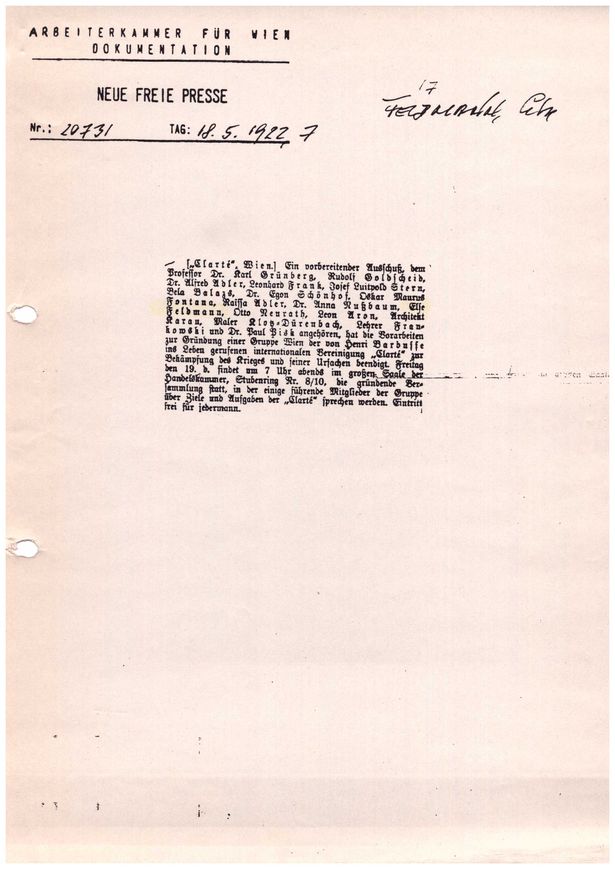

Another important aspect of Else Feldmann’s life is her promotion of lively exchange among committed writers. At the age of 38, she was a founding member of the Austrian faction of the French association Clarté, an association of intellectuals founded in 1919 by Henri Barbusse and Romain Rolland to fight against war. Earlier this year, she and other authors founded the Association of Socialist Writers,in order to give all authors with a socialist worldview a place where they can exchange views, as well as promote themselves intellectually and materially, making evenings such as this one possible.

Finally, we can wish the esteemed as well as successful journalist and writer Else Feldmann continued success in her future work, and we are very much looking forward to her new serial novel Martha und Antonia (‘Martha and Antonia’), which will be published in the Arbeiter-Zeitung starting this fall.

‘However, what is at the end of all these new things? Oh, nothing.‘

m

Else Feldmann, Martha und Antonia

Else Feldmann

born 25 February 1884, Vienna

died 14–17 June 1942, Sobibór death camp

Biography

Else Feldmann was born in Vienna on 25 February 1884. She was the second of seven children born to the merchant and trader Ignatz Friedmann (1842/48–1935) and his wife Fanny (née Pollak, 1859–1940). After her father lost his job as a salesman, she discontinued her education at a teachers’ training institute and, at the age of 16, began working in a factory in order to financially support her family. In 1904, the young Else was introduced to the circle of the Jewish social reformer Josef Popper-Lynkeus (1838–1921). There she met well known authors such as Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931), Otto Neurath (1882–1945), and Stefan Zweig (1881–1942). Popper-Lynkeus’s ideas for a more just society significantly influenced Feldmann’s views and were reflected in her literary and journalistic activities. In 1908, she wrote her first short stories and journalistic contributions, which from 1912 onwards were regularly published in newspapers such as Der Abend, Der Tag, Arbeiter-Zeitung, and Die Frau. Her socially critical articles addressed child poverty, youth delinquency, and life in the impoverished districts of Vienna.

g

On 12 February 1916, her only fully preserved play, Der Schrei, den niemand hört. Trauerspiel aus dem Ghetto (‘The Cry That No One Hears: A Tragedy from the Ghetto’), premiered at the Volksbühne in Vienna. For this performance, Lia Rosen, a former Burgtheater actress, was engaged from Berlin. Two other plays, Jazzmusik: Ballett der Straße (‘Jazz Music: Ballet of the Street’) and Der Mantel (‘The Coat’), are only fragmentarily preserved. In 1921, her best-known novel, Löwenzahn. Eine Kindheit (‘Dandelion: A Childhood’), was published by Wiener Rikola Verlag.

g

Starting in the 1920s, Feldmann was active in organizations such as Clarté and the Associationof Socialist Writers, where she and her fellow writers advocated for a fairer world. Due to increasing restrictions on press freedom and severe censorship, Feldmann’s economic situation deteriorated. In 1938, her works were placed on the ‘List of Harmful and Undesirable Literature’, leaving her with few opportunities to publish her texts. On 14 June 1942, Else Feldmann was deported to the Sobibór extermination camp in Eastern Poland, where she was murdered by the Nazi regime.

© Theodor Kramer Archiv, E.FE.II/7

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

What remains?

k

Else Feldmann enjoyed great success during her lifetime, but she also experienced periods of crisis. As a writer and journalist, she dealt primarily with social issues and formulated ideas that would contribute to a fairer world. In her reportage, Feldmann described, unlike her male colleagues, the environment she herself came from, and furthermore directed her readers’ attention to the fate of children, mothers, and women. In doing so, she adopted a remarkable perspective that focused not only on the external conditions of society, but also on their effects on people’s psyches.

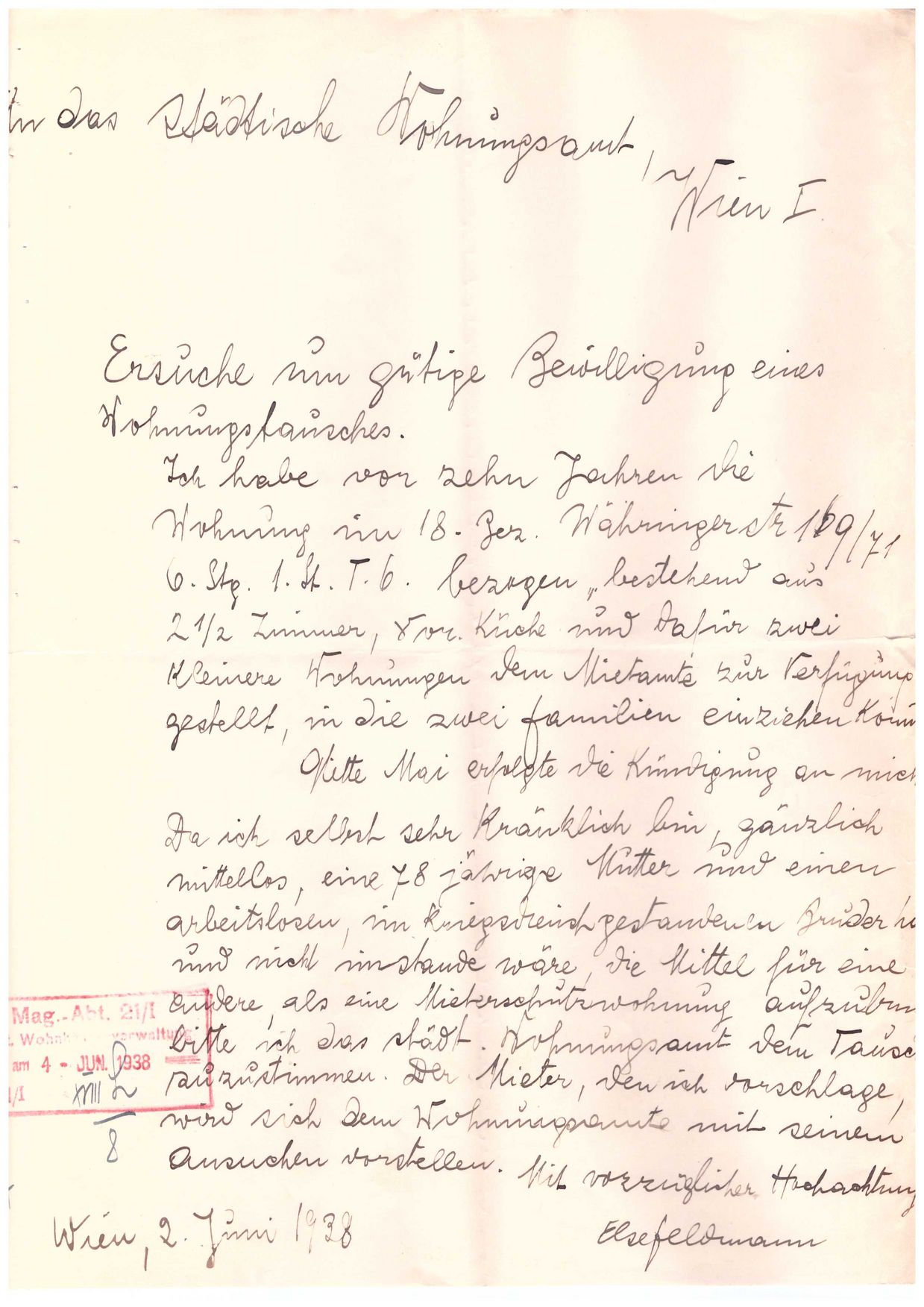

Her last years in Vienna were marked by economic problems, but also private issues. Her publishing activities were forcefully restricted and her works were banned. Additionally, she had to take care of her sick mother and her war-disabled brother. In 1933, she cofounded the Association of Socialist Writers with other authors, which drew attention through committed anti-fascist actions such as lectures. Just one year later, this association was dissolved and banned by the Austrofascists. In March 1934, Else Feldmann tried to publish her last novel, Martha and Antonia, with Allert de Lange, an Amsterdam publisher of German-language writers in exile, but this request was rejected. After her works were placed on the ‘List of Harmful and Undesirable Literature’ in March 1938, her writing career was over.

In March 1938, her and her mother were given notice to leave their apartment. After being evicted on 22 June 1938, the two women were forced to permanently change their residence. On 14 June 1942, Feldmann was arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Sobibór death camp in eastern Poland. Due to the lack of reliable sources, there is no exact date of her death, but it is estimated to have occurred between 14 and 17 of June 1942. Else Feldmann died alone and childless, one of the many victims of the Holocaust.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Sofia Rübig

for drawing my attention to Else Feldmann.