Wien, 5. Oktober 1923

A Dramaturge at Work

Behind the Scenes at the Deutsches Volkstheater

with Heinrich Glücksmann

Our reporter, Isabelle Wirth, visited the dramaturge Heinrich Glücksmann at the Deutsches Volkstheater

© KHM-Museumsverband

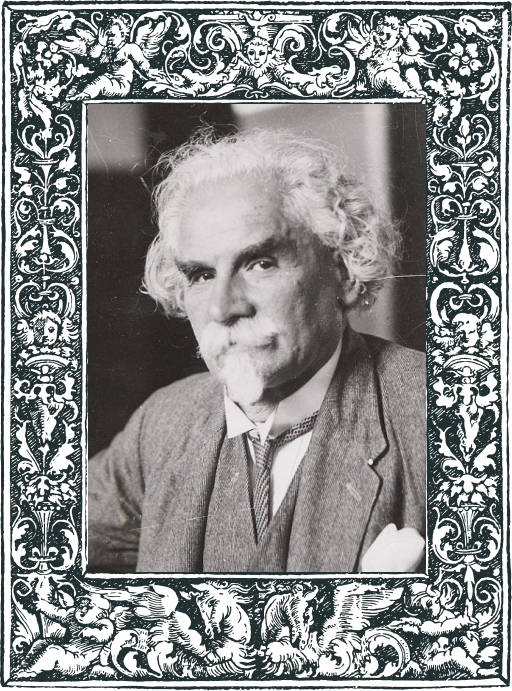

Our reporter, Isabelle Wirth, visited the dramaturge Heinrich Glücksmann at the Deutsches Volkstheater to observe his work, congratulate him on his 60th birthday, and discuss his role as a promoter of emerging talents.

The Backstage

We find Heinrich Glücksmann backstage, where he has just concluded a meeting with the actors and is now meticulously organizing his notes. From the natural way he moves here, two things become evident: first, he must know the theatre like the back of his hand, and second, he seems to merge with it – they are inseparably connected. Glücksmann is a theatre person through and through. This is precisely why his professional biography is all the more impressive. Not only does he write his own dramas, but he also works as a journalist for various newspapers. The most remarkable exception in this field was probably his work in the early 1880s for a women’s magazine, where he created a female narrative voice. This work can be seen as proof of his versatile talents. Glücksmann doesn’t only work for the theatre and newspapers; he also occasionally delves into the film industry.

Mozart’s Life, Loves, and Sorrows

Glücksmann wrote the screenplay for the highly promoted feature film Mozarts Leben, Lieben und Leiden (‘Mozart’s Life, Loves, and Sorrows’), which was directed by Otto Kreisler and released two years ago. However, this wasn’t his first excursus from the theatre stage to the silver screen. In 1918, he wrote the screenplay for So fallen die Lose des Lebens (‘The Fortunes of Life’), a silent film melodrama directed by Friedrich Rosenthal. Currently, he tells us that he is dedicating his time to other projects. Whatever happens, we can eagerly anticipate Glücksmann's next artistic work.

g

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

The 60th Birthday

On the occasion of his 60th birthday, which took place in July of this year, Glücksmann can look back on a long, diverse, and, above all, successful career. Not only did we congratulate him on his special day, but also many of his acquaintances, whose names might be familiar to some, did so as well. Listing them all would exceed the scope of this article, so we’ll mention just three as representatives: the writer Alfred Klaar, the poet Max Mell, and Glückmann’s equally talented fellow dramatist, Else Feldmann. Another well-wisher was the writer and playwright Arthur Schnitzler, whom Glücksmann has always supported as a promoter, critic, and friend.

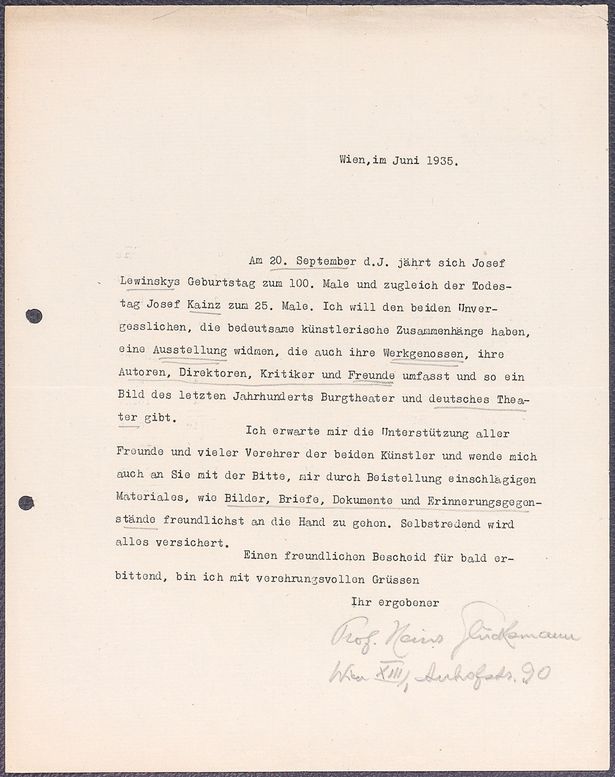

A Custodian of Memories

Glücksmann not only fosters talented contemporaries but also helps preserve the memory of those who have already passed away. For example, he spoke at the funeral of his friend, the actor Josef Kainz, and continues to honour his memory. Therefore, he stands out not only through his diligence and artistic work but also through his humanitarian efforts. In the spirit of humanity, one can only hope that Glücksmann’s work rubs off on all of us.

k

‘As I embark upon looking back at the path of my life, recounting how I came to the theatre, it suddenly dawns on me that, in fact, the theatre came to me.’ – Heinrich Glücksmann, ‘Wie ich zum Theater kam’

o

Heinrich Glücksmann, ‘Wie ich zum Theater kam’, Neue Illustrierte Zeitung, 20 July 1924

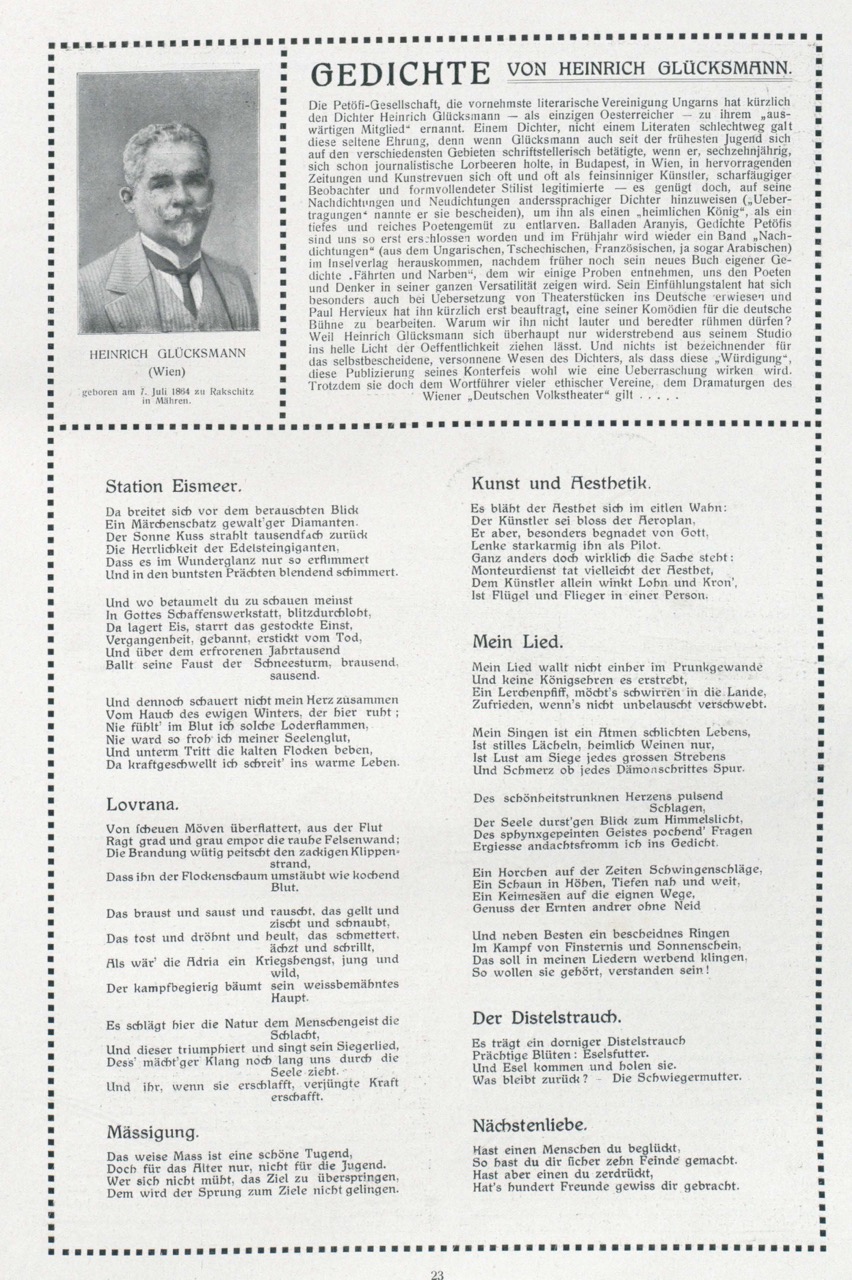

Heinrich Glücksmann

born 7 July 1863, Rakschitz

died 3 January 1943, Buenos Aires

Biography

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

g

Heinrich Glücksmann was born on 7 July 1863, in Rakschitz, Moravia, under the name Hermann Heinrich Blum. His father, Leopold Blum (dates of life unknown), worked as a merchant and farmer. In the late 1870s, Heinrich moved to Vienna, where he took acting lessons from 1880 to 1882. During this time, he earned his living through journalistic work. Under the pseudonym Henriette Namskilg, he wrote for the Wiener Hausfrauen Zeitung. Glücksmann also lived in Hungary for some time, where he worked as an editor for the Politische Volksblatt Budapest.

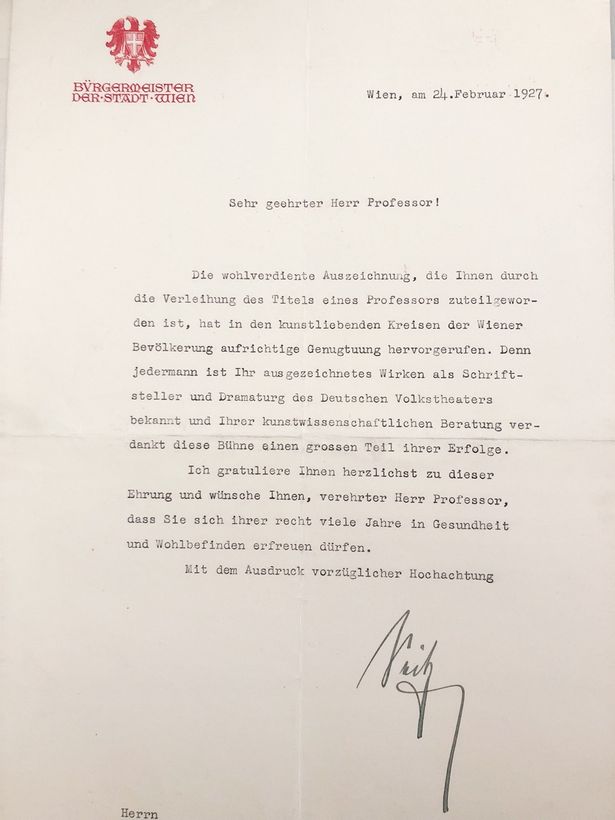

In 1888, he wrote his first play, titled Therese. By the end of the 1880s, he was back in Vienna, writing for some of Austria’s most prominent newspapers, such as the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung and the Neue Freie Presse. During the same period, he began his work as an editor at the Deutsches Volkstheater, a role he held until 1935, and where he also worked as a dramaturge. He contributed to the success of plays by Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931), Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), and Karl Schönherr (1867–1943). In 1895, he married Helene Rechnitz (1869/72–?), with whom he had four sons. From 1900 to 1917, Glücksmann served as the editor-in-chief of the magazine Der Zirkel (‘The Circle’), published by the Freemasons, who stood for tolerance, freedom, equality, and humanity. He himself belonged to the Freemason society Humanitas and was a member of the Concordia Writers’ Association and an official of the Deutsch-österreichischen Bühnenverein. In his publications, he commemorated deceased artists, including his friend, the actor Josef Kainz (1858–1910), to prevent them from fading into societal oblivion. As a committed pacifist, Glücksmann advocated for peace and humanity and worked closely with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bertha von Suttner (1843–1914) in her Peace Society. Due to his outstanding contributions, Glücksmann was awarded the honorary title of Professor in 1927 and was named a citizen of Vienna in 1933. As part of this recognition, a bust with Glücksmann’s likeness, created by Nicolaus Koni (1911–2000), was unveiled but, unfortunately, it is now considered lost. Following the Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany, Glücksmann and his wife fled to Argentina in 1941, where he passed away on 1 March 1943, at the age of 80, in Buenos Aires.

What Remains?

k

Heinrich Glücksmann was a true polymath, highly successful and widely acclaimed, particularly in the Vienna theatre scene – and he was Jewish. This fact provided the Nazis with a pretext not only to strip him of his freedom, fundamental human rights, and homeland, but also to erase his place in the collective memory. As recently as 1933, he had been awarded honorary citizen of the city of Vienna, the second-highest honour for distinguished service. In recognition of this, sculptor Nicolaus Koni was commissioned to create a bust with Glücksmann’s likeness, which was displayed at the Deutsches Volkstheater, where he worked as a lecturer and dramaturge until 1935. Today, the bust is considered lost, leaving us to speculate about its fate and ultimate whereabouts.

The Anschluss in March 1938 had profound consequences for Heinrich Glücksmann. That year, among other hardships, the Glücksmann family was evicted from their apartment on Auhofstraße. Many of Glücksmann’s colleagues left Vienna and emigrated to other countries, including his youngest son Hans Karl and his family, who fled to Argentina via Great Britain in 1939. Glücksmann and his wife Helene could only join them in 1941. There is little information about their escape. Heinrich Glücksmann passed away at the age of 79 on 1 March 1943, in exile in Buenos Aires. Despite his extensive body of work, his significant influence, and his importance in the world of theatre at the time, Heinrich Glücksmann is scarcely remembered today. The only traces of Glücksmann that remain can be found in the correspondences and old newspaper articles preserved in archives.