Vienna, 25 April 1934

How an Anti-Semite Became a Fighter Against Anti-Semitism

An obituary for Hans Liebstöckl by our correspondent Christian Müller

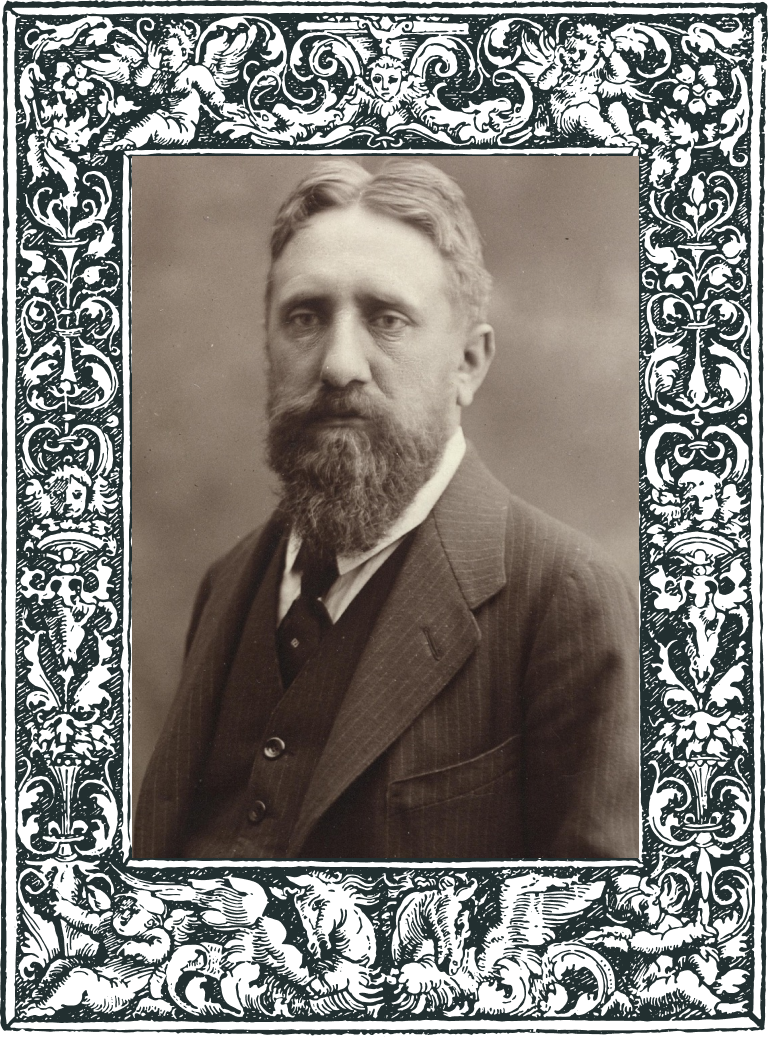

© ÖNB-Bildarchiv / picturedesk.com, sign. Pf 7530:B (1)

The triumph of the good and beautiful, as well as the transformation of characters emerging from the shadows, are often simple and fictional narratives. In times like these, when the world around us seems to be growing darker, it is essential to highlight individuals who offer a glimmer of hope. The life of Hans Liebstöckl embodies hope, compassion, transformation, and the rejection of hatred.

On 5 November 1892, the Association of German University Students, as reported in the Ostdeutsche Rundschau, celebrated the days of German nationalism in Prague with ‘massive participation’. Liebstöckl joined in the festive spirit, delivering a lively speech and giving an hour-long lecture on ‘German Folk Culture’ a few days prior. Liebstöckl was deeply rooted in the German-nationalist milieu. In addition to his writings, one can find Hans Liebstöckl’s name in the committee of German university students in Graz and in the election results of the Vienna branch of the Bund der Deutschen in Böhmen. Many of the publications and associations he was involved in were thoroughly anti-Semitic. Hans Liebstöckl was an activist.

Karl Lueger, the mayor of Vienna at the time, referred to him as a ‘full-blooded Aryan’ on the occasion of his wedding to Olga Klebinder, a Jew who had converted to Catholicism. Liebstöckl’s writings in German-nationalist and anti-Semitic publications, as well as his involvement in German-nationalist associations, undoubtedly solidified his position as a ‘raw diamond’ within the machinery of German nationalism. In 1895, he delivered a speech to resounding applause, once again enumerating the tasks of the Bund der Deutschen in Böhmen.

Then Came Silence…

g

No more German-nationalist speeches and no contributions to the Bund der Deutschen in Böhmen or Germania. Following his marriage to Olga Klebinder and his new involvement with the Reichswehr, Hans Liebstöckl’s clear transformation becomes evident. In 1904, his last connection to a ‘German Association’ can be found – the German Pedagogical Association. Liebstöckl was now an editor at a Catholic-conservative newspaper. The anti-Semitic Reichspost complained in a 1900 article that, ‘eleven Jews and four Christians’ were employed there, and most of the Catholics were even married to converted Jews. A pattern of pointing out the distance between Liebstöckl’s present and his past, and the change in sentiment towards him as a result, can be found repeatedly in the media of the time, and the anger of his old ideological comrades is thus easy for us to see. By 1904, the Reichspost proclaimed that Liebstöckl was, after all, a ‘Christian’ – the word ‘Christian’ is placed in quotation marks, as if it were being questioned – but had married a Jew. Furthermore, it is written that Liebstöckl had previously ‘even’ written for anti-Semitic newspapers.

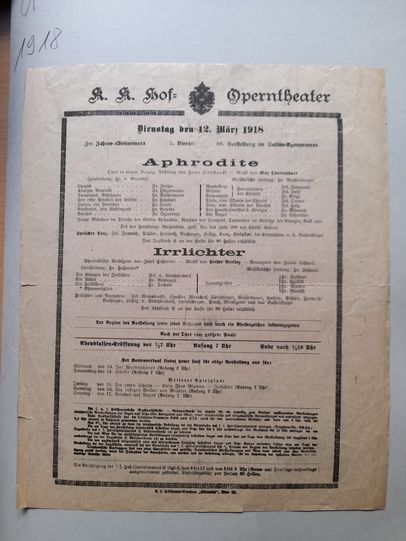

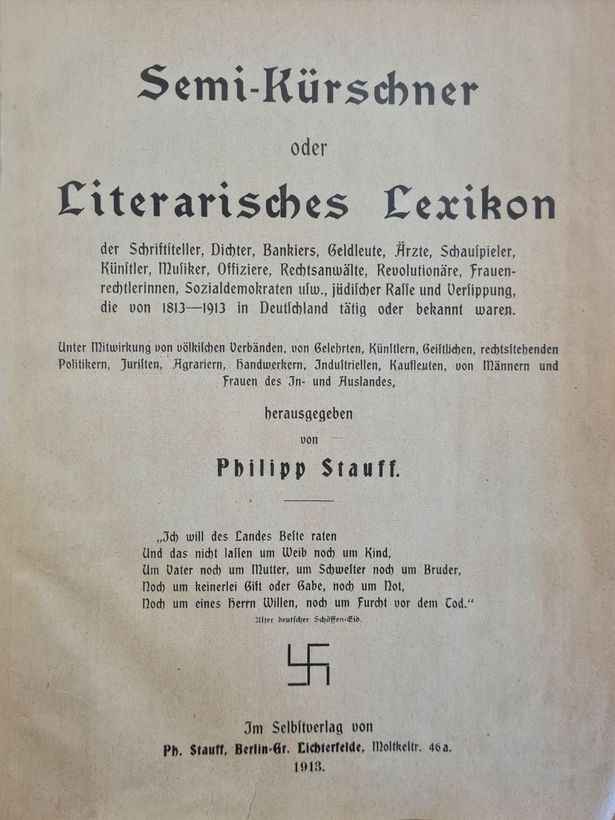

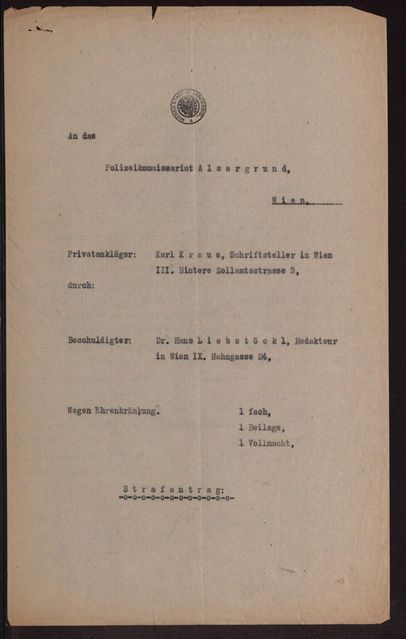

Liebstöckl forged new friendships but also encountered enmities. He produced an incredible amount of literary work: critiques, articles, operas, operettas, and, let us not forget, the outstanding opera Aphrodite from 1912! ‘Liebstöckl is now very much in vogue, among the Jews, he is like the child in the house...’ wrote Die Fackel in 1923. The magazine also dedicated itself to Liebstöckl’s articles for the Reichswehr and his fight against anti-Semitism and German chauvinism among the ‘Germans’. Even though Liebstöckl had only recently been part of this ‘dubious’ society, his name appears in the despicable anti-Semitic work, the Semi-Kürschner, in 1913. His literary work and activities were multifaceted: he poured his fascination with mysticism into books, and his work as editor-in-chief for Die Bühne remains unforgettable, as do the countless debates that culminated in Karl Kraus’s defamation trial a decade ago. He continued to work unwaveringly against anti-Semitism until yesterday, when this polarizing personality left us.

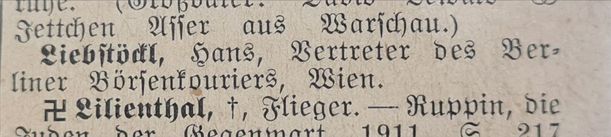

Art. ‘Hans Liebstöckl’, in Philipp Stauff (ed.), Semi-Kürschner oder Literarisches Lexikon der Schriftsteller, Dichter, Bankiers, Geldleute, Ärzte, Schauspieler, Künstler, Musiker, Offiziere, Rechtsanwälte, Revolutionäre, Frauenrechtlerinnen, Sozialdemokraten usw., jüdischer Rasse und Versippung, die von 1813–1913 in Deutschland tätig oder bekannt waren (Berlin-Lichterfelde, 1913), Part 2, column 294. Vienna University Library, sign. I-394922/1.1913

‘Liebstöckl, the virtuoso of jargon, is a fervent German, one who, in his German conviction and German essence, forms a rarity within the circle in which he moves.’

n

Rudolf Holzer, Die Fackel, 1923

Hans Liebstöckl

born 26 February 1872, Vienna

died 24 April 1934, Vienna

Biography

‘They love the chosen people whom God has chosen to be poets, journalists and theatre directors.’

Julius Bauer, Die Bühne, 1924

e

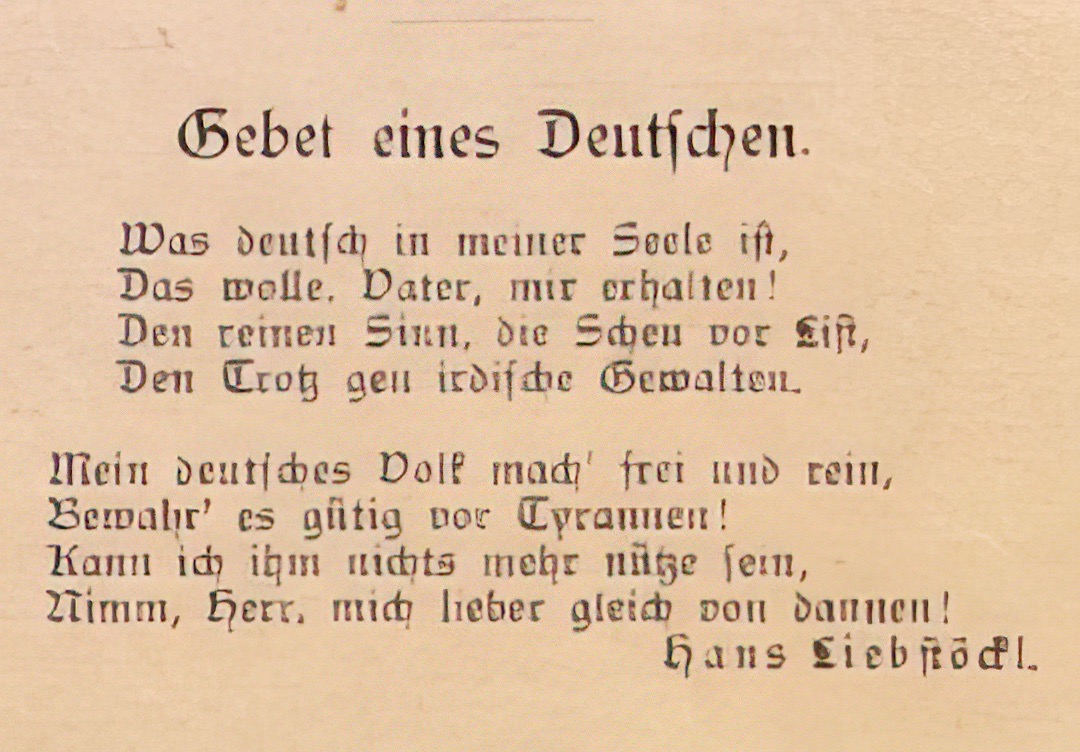

Hans Liebstöckl was born on 26 February 1872, in Vienna, the son of Colonel Friedrich Johann Liebstöckl (dates of life unknown) and his wife Paula (née Fischer, dates of life unknown). After spending his early school years in Vienna, he attended a gymnasium in Prague. In both cities, he pursued studies in law, philosophy, and violin. It was during this time that he first encountered journalism. Liebstöckl was a German-nationalist student, a member of the Burschenschaft Germania (one of the traditional student associations of Austria), secretary of the Vienna branch of the Bund der Deutschen in Böhmen, and at that time, a staunch anti-Semite. He published poems and short stories, including Das deutsche Gebet (‘The German Prayer’) in 1892, in the newspaper Ostdeutsche Rundschau.

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

During a stay in Vienna, Gustav Davis (1856–1951), a Jewish journalist and writer and the editor of Reichswehr, discovered Liebstöckl’s journalistic talent and hired him. This marked a turning point in Liebstöckl’s life. He distanced himself from his German-nationalist past and began advocating against anti-Semitism. In 1899, he married a Jewish singer and vocal coach, Olga Klebinder (1877–1964) in the Roman Catholic parish of Lichtenthal in Vienna’s 9th district. In 1900, their son Friedrich was born, followed by their daughter Louise (née Berger, 1902–1974) two years later.

In 1913, Liebstöckl’s name appeared in the directory of the Semi-Kürschner, an anti-Semitic pseudo-reference work that listed undesirable and persecuted individuals. This was due to his political and ideological transformation from a radical anti-Semite.

g

In 1924, Liebstöckl embarked on his successful career as the editor-in-chief of the newly established Viennese entertainment magazine Die Bühne (‘The Stage’). This newspaper epitomized the spirit of cosmopolitan Vienna like no other. The brief but poignant editorial of the weekly publication, which first appeared on November 6, 1924, proclaimed, ‘Die Bühne is everything that has an audience’, and it delved into ‘Theatre, Art, Fashion, Film, Society, and Sports’. In his theatre reporting, Liebstöckl focused on combating anti-Semitic prejudices. His contemporaries Ludwig Ullmann (1887–1959), Julius Bauer (1853–1941), and Rudolf Holzer (1875–1965) left evidence of their appreciation, humorously referencing Liebstöckl’s affection for the ‘chosen people’.

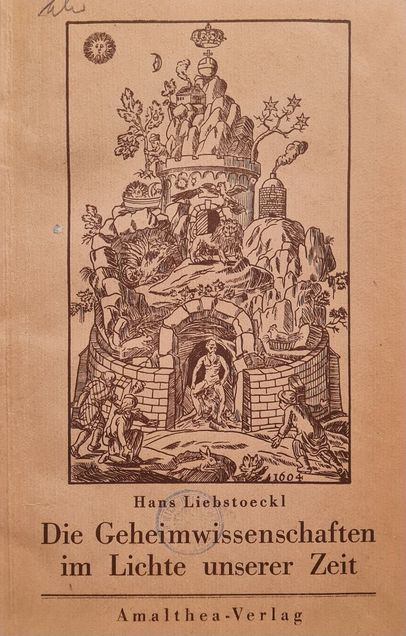

In addition to culture, Liebstöckl had a keen interest in the history of mysticism. In 1932, he published the book Die Geheimwissenschaften im Lichte unserer Zeit (‘The Occult Sciences in the Light of Our Time’). Liebstöckl’s versatility shone through his diverse writing. He wrote texts for operas and operettas, including Aphrodite and Der Schmuck der Madonna (‘Madonna’s Jewelry’). On 24 April 1934, Hans Liebstöckl passed away in Vienna due to a heart condition.

Source: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus / Public Domain Mark 1.0.

What remains?

k

It was not only Hans Liebstöckl who was a dazzling personality in cosmopolitan Vienna, but also his wife Olga Liebstöckl, who, like her husband, has been forgotten. Olga worked as a singer at the Prague National Theatre and the Vienna Volksoper. During World War I, she sang in field hospitals, for which she was awarded a Red Cross medal. Hans Liebstöckl, who passed away from heart disease on 24 April 1934, in Vienna, left behind not only Olga but also their two children, Friedrich and Louise.

Shortly after the Anschluss, Friedrich and his wife Marie fled due to political persecution. His life in exile remains unknown to this day. In contrast, Olga and Louise did not leave. Mother and daughter remained in Vienna and continued to be members of the Christian-conservative Harand Movement, the ‘World Movement Against Racial Hatred and Human Misery’. In March 1943, the two women were denounced by a neighbour for ‘operating a secret radio transmitter’. Subsequently, they were arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, where they were imprisoned until their liberation in July 1945.

The women returned to Vienna and lived in the KZ-Rückkehrerheim (‘Concentration Camp Returnees’ Home’) at Seegasse 9.

g

According to the victim support records, Olga tried in vain until the end of her life to obtain compensation for her apartment at Hahngasse 24, where she had lived with her husband and children for over 40 years. In 1961, Olga Liebstöckl made one final attempt and wrote a poignant thirteen-page letter to the relevant authorities, recounting her life.

In trembling handwriting, she wrote:

‘I am 85 years old and have such dizziness that I cannot take five steps without falling. I have completely lost my sense of direction, so I wouldn’t be able to find my way home. I am so forgetful and have such worries about my daughter, who suffers from the severe nerve disorder Parkinson’s, is partially paralyzed, and has been unable to leave the house for three years, experiencing excruciating pain. What will happen to her when I am no longer here?’

Source: ANNO/Österreichische Nationalbibliothek

She talked about her childhood in Prague, her career as a musician and vocal coach, and her life with her husband, Hans Liebstöckl. She also recounted the horrific conditions in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, where she witnessed a prisoner being consumed by lice.

She described her living conditions in Vienna in the 1960s as follows:

‘I now live with my daughter, who was a well-known actress, in complete seclusion, still plagued by the trauma of imprisonment.’

Without ever receiving compensation, Olga Liebstöckl passed away on 28 September 1964, in the Baumgarten nursing home.

Ten years later, her beloved daughter Louise also passed away.

‘There lies a town, so tiny and small,

Surrounded by barracks, enclosing it all.

They say to the Jews, “This place is your fate,”

And lock 70,000 Jews within the gate.

They tell them, “Jew, now perish and die,

Choke on the germs and filth, by and by.

In bugs, in fleas, and in lice’s domain,

You’re the state’s enemy number one,” they proclaim.

The city grants Hitler its unconditional prize.’

Louise wrote this poem in Theresienstadt

e