Vienna, 31 December 1933

Our Jubilarian Armin Friedmann!

A tribute by Jenny Unterkofler on the occasion of his 70th birthday

![[Translate to English:] Schwarz-Weiß Fotografie von Armin Friedmann](/fileadmin/_processed_/2/4/csm_A_Friedmann_Header_f2bb00eb06.png)

© ÖNB-Bildarchiv / picturedesk.com, Media number: 00189379, Object name: 204691-C

‘[H]e ran with weasel-like speed in the alley, in the newsroom, from one room to another, with an unimaginable speed, agility and nimbleness.’

n

Rudolf Holzer, Wiener Zeitung, 1 January 1947

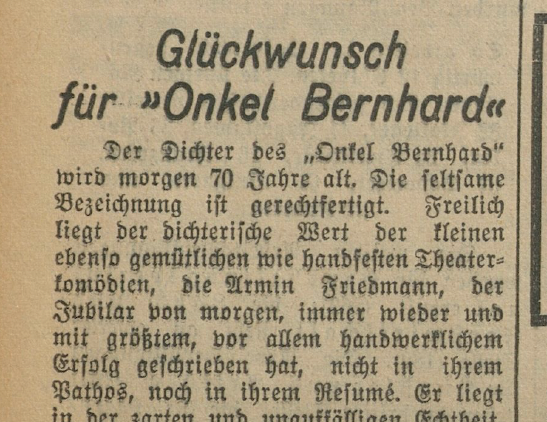

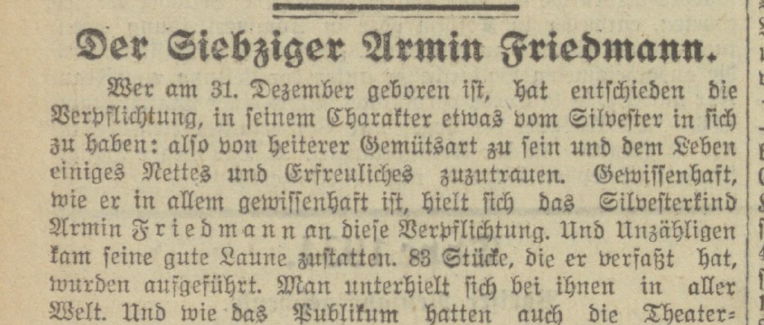

Today, on the last day of the year 1933, Armin Friedmann turns 70. Since today’s mail delivery to Friedmann residence is undoubtedly burdened due to the numerous letters of congratulations, we congratulate the jubilarian with this tribute to his extensive body of work by paying special attention to one of his celebrated comedies.

The success of the comedy Schottenring was a stroke of luck by Friedmann in his usual collaboration with Louis Nerz (1866–1938). It had its world premiere at the Kammerspiele on 12 January and has since embarked on a long journey. The witty and clever three-act industrialist comedy brings to the theatre lifelike characters who shine through the strong plot and spectacular effects. The accuracy of the roles was due in no small part to the brilliant performances of all those involved, who gave us an incomparable and extraordinary experience on stage. It embodied a piece of Viennese local history with all our favourites: Gisela Werbezirk, of course, who, in the unforgettable leading role as the old Proßnitzer, continued to enhance her reputation night after night. The fantastic reappearance of Mizzi Günther after her years-long absence from the stage has also given us great pleasure, as has the rest of the ensemble, who were uniformly dazzling and who have been called back for numerous further performances due to the play’s resounding success.

![[Translate to English:] Aufnahme aus dem Theaterstück 'Schottenring' mit den Schauspielern Werbezirk, Springer und Kramer, abgedruckt in der Wiener Allgemeinen Zeitung vom 14. Januar 1933, Seite 6](/fileadmin/user_upload/Bildschirmfoto_2023-10-23_um_14.11.47.png)

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

However, rather than dwelling for too long on the splendid production itself, let us trace the journey of this Viennese industrialist comedy into the big wide world. Every evening the performances at the Kammerspiele were marked by loud applause, as many reporters and experts had already predicted. The play was so popular at the beginning of the year that the director Aurel Nowotny had to postpone a planned guest performance to continue with the celebrated premiere cast. Shortly thereafter, the play’s 25th performance occurred. While the triumph seemed endless, it was briefly cancelled despite its immense success, only to be reinstated in the Kammerspiele’s repertoire. On 15 March, the 50th performance of the play took to the stage! Once again, a final performance was scheduled for 26 March, but a glance at the Viennese newspapers revealed that it remained a highlight in the schedule until mid-April. A brilliant success!

g

In April, the journey from Schottenring to foreign countries began. Not only did the Hungarian Theatre in Budapest plan a Hungarian premiere, but a Dutch translation and adaptation were also implemented in order to let the play shine on the Amsterdam stage as Die drei Proßnitzer (‘The Three Proßnitzers’). It became an international success with numerous adaptations and guest performances, especially for the hard-working Gisela Werbezirk herself. In April, for example, she appeared on the German Stage in Prague. In Karlovy Vary, Marienbad, and Franzensbad, she performed her signature role to sold-out audiences and received always great applause. Finally, in September, she completed a multi-day guest performance at the city theatres of Bolzano and Merano, as well as in the Inner City Theatre in Budapest.

What makes this play so successful? After extensive research, we came across Armin Friedmann’s recipe for success, which he had already disclosed last year in the program sheets of the Neues Lustspielhaus: ‘If everyone in the house says, “This time it’s nothing!” – then it’s sure to be something!’

Armin Friedmann

born 31 December 1863, Budapest

died 30 May 1939, Vienna

Biography

On the last day of 1863, Armin Friedmann was born in Budapest, the first child of Josefine (née Taub, 1842–1894) and David Friedmann (1828–1889). A short time after his birth, the family moved to Vienna. David Friedmann was employed as a gold and silver worker at the jeweller Taub & Comp on Stephansplatz. In 1874 he established his own business on Stephansplatz 9. He intended to make his son Armin is his successor, and at the Realschule in Ballgasse Armin acquired the necessary commercial knowledge for the job. However, instead of taking over the business, he discovered his passion for art on trips to Italy, France, and Spain. Despite not having passed the matura (the exam given at the end of secondary education), he attended lectures by the renowned art historians Franz Wickhoff (1853–1909) and Alois Riegl (1858–1905) as a non-degree student. His pronounced thirst for knowledge and broad interests made this autodidact a highly competent intellectual.

In 1898 Friedmann became an art critic for the renowned Wiener Zeitung. For 22 years he wrote about current art events – always with great sympathy for the young and the new.

g

His colleague and later editor-in-chief Rudolf Holzer (1875–1965) remembers him as a dazzling ironist who never made scornful judgments, a sharp contrast to the scathing tone of cultural critics like the powerful Karl Kraus (1874–1936). In 1919 Friedmann switched to the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, where he continued to write theatre reviews. Starting in 1910, he also worked as a playwright, and one of his earliest plays, Onkel Bernhard (‘Uncle Bernhard’) became an enormous success. Over the next 25 years, he wrote around 100 plays for stars such as Hansi Niese (1875–1934), Gisela Werbezirk (1875–1956), and Alexander Girardi (1850–1918). Friedmann delighted the cosmopolitan Viennese audience with so-called jargon plays, which countered the anti-Semitism of the German-national minded with rapid wit.

Wie schreibt man ein Judenstück (‘How to Write a Jewish Play’) was published by Friedmann as a dramaturgical recipe for his admirers and enviers in a program booklet in 1932. In February 1938, his latest comedy Der Blaue Knabe (‘The Blue Boy’) was announced, in which Hans Moser (1880–1964) was to take the leading role.

g

On 12 March, the Anschluss brutally destroyed Armin’s existence. What he and his wife Therese (née Reichel, 1870–1942), whom he married on 20 April 1890, had to experience in their everyday life under the Nazi regime has not been handed down. Armin Friedmann died on 30 May 1939, and his wife was murdered in the Holocaust. The marriage remained childless. It was Friedmann’s colleague and good friend Rudolf Holzer who remembered Friedmann in a detailed obituary in the Wiener Zeitung in 1947 and preserved his literary estate.

What remains?

k

A year after the Anschluss, Armin Friedmann died of heart failure in Vienna on 30 May 1939, at the age of 75. The condolences to his wife Therese, which are in the archives of the Theatre Museum, provide an insight into the great admiration and appreciation of the late journalist, writer, and playwright. However, these took place quietly and privately.

The writer Felix Salten (1869–1945), for example, wrote the following words to Therese:

‘Only rarely are there people of such high intellectual standing, of such nobility of soul as Armin Friedmann was. He had such a subtle feeling for life, for reality and for its shaping in any form. Receptive, serene, his sense was open to the personalities, the works, the phenomena of nature, and was supported by an unusually deep knowledge.’

It was not until after the end of World War II that Rudolf Holzer published a detailed obituary in the Wiener Zeitung: ‘With wistful satisfaction one remembers today that this ardent Viennese, this enthusiastic journalist, was spared the fate of annihilation by robbers and murderers, that Friedmann, just before the worst, died in his beautiful home, cared for by his clever, quiet, kind wife; she was not spared the hard end.’

g

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

After the Anschluss, the Friedmann family, like all Jews with property of more than 5,000 Reichsmarks, had to declare their assets. Armin Friedmann was an avid collector of historical books, old instruments, shells, and paintings. On 5 October 1938, National Socialist officials from the so-called Vermögensverkehrsstelle (the Nazi office for organized robbery, under Goering’s responsibility) entered the Friedmanns’ apartment to ‘check’ for art objects. The file lists artworks by Gustav Klimt, Tina Blau, and Honoré Daumier. The National Socialists also noted in red letters a valuable, unspecified Dutch painting.

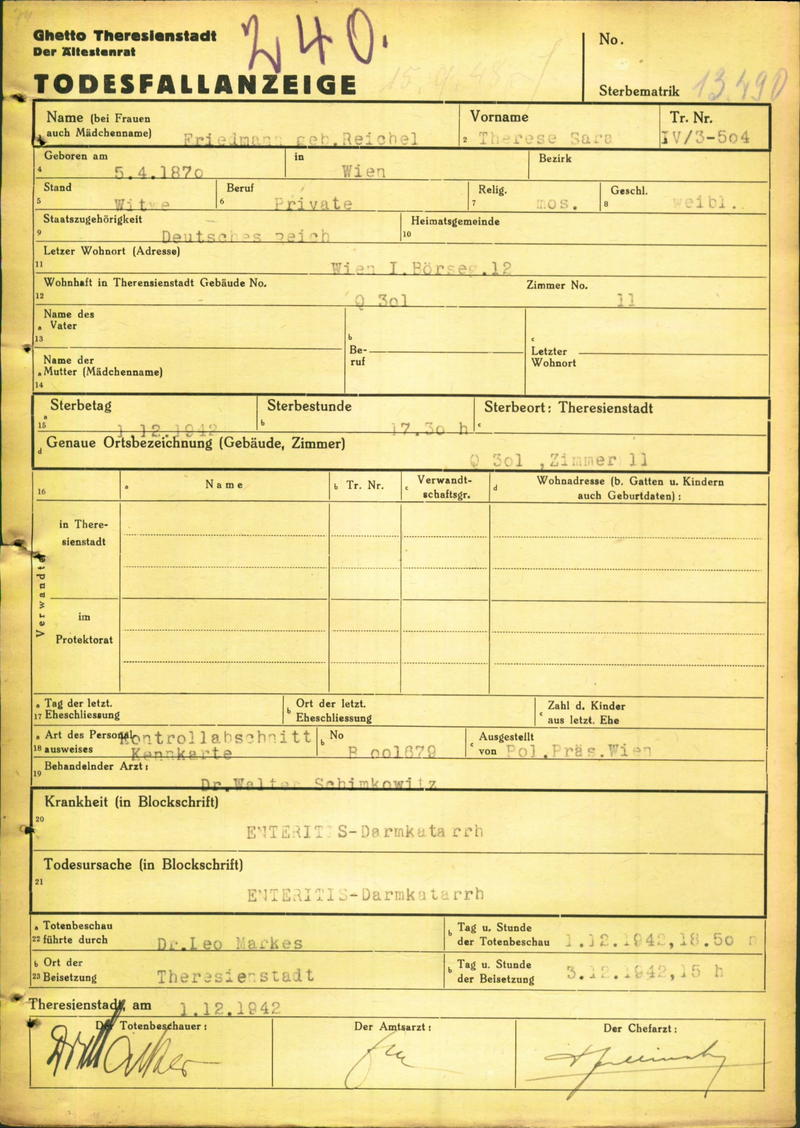

Therese Friedmann was deported to Theresienstadt on 10 July 1942. The only note of her demise is the death notice from Theresienstadt: ‘died 1 December 1942, cause of death: enteritis intestinal catarrh’.

To this day, the whereabouts of the Friedmann family art collection is unknown. Henriette and Alexander Wolff, Therese Friedmann’s niece and nephew, filed an application for restitution of the former residence at Börsegasse 12, on 26 August 1947. Today, there is nothing there that reminds us of the Friedmann couple.

With the death of Armin Friedmann, according to Rudolf Holzer, ‘a cultural reminiscence of the former Vienna and its great journalism’ passed away. Today, there is no trace of him or of his art collection, which he had accumulated over the years, and which was stolen by the National Socialists.