Berlin, 30 August 1929

From Child Prodigy to Composer

Artist profile of music virtuoso and life enthusiast Camilla Frydan

by Eva Leitner, Johanna Suppin and Isabelle Wirth

© Edith Barakovich / Ullstein Bild / picturedesk.com

Independent with Every Fibre of Her Being

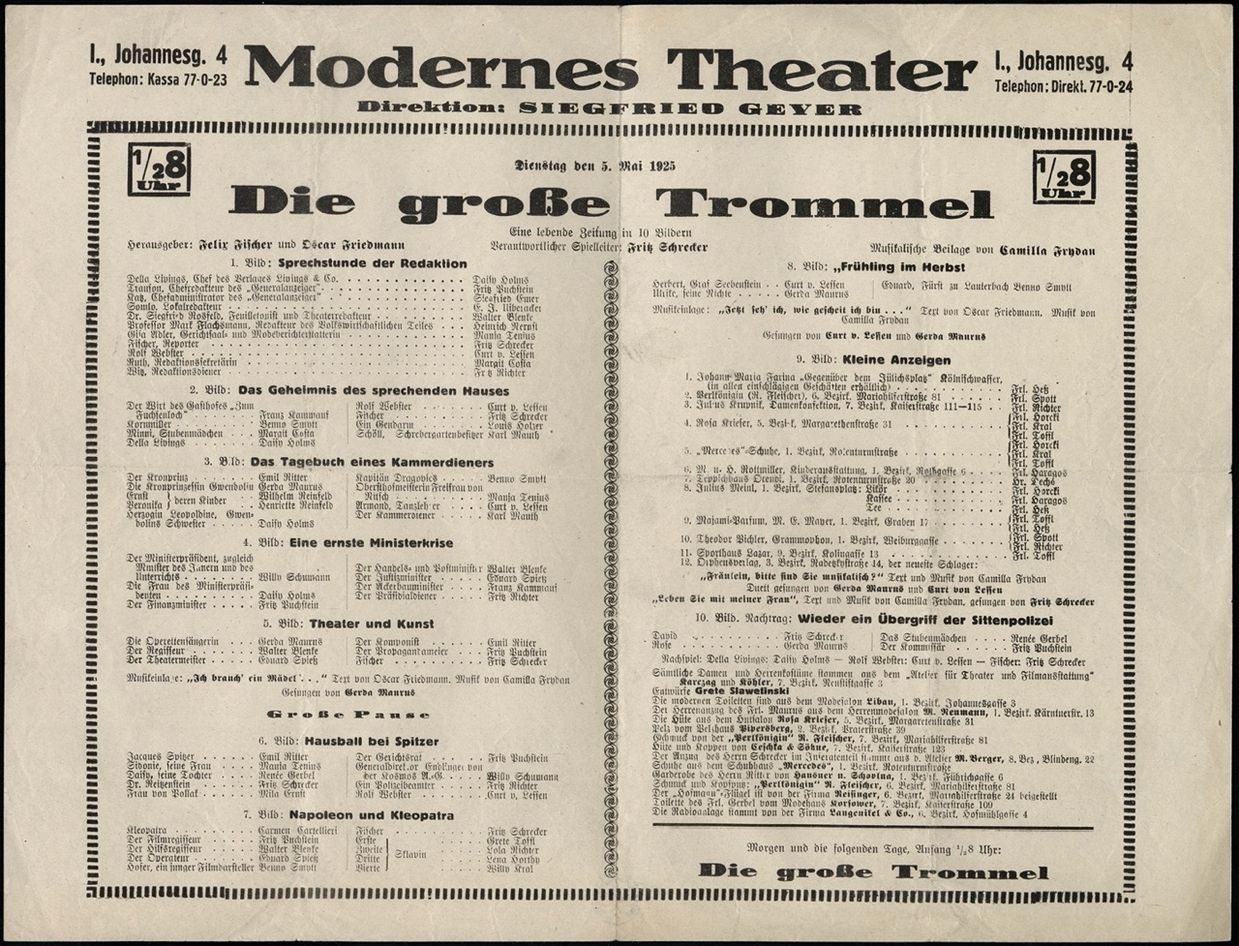

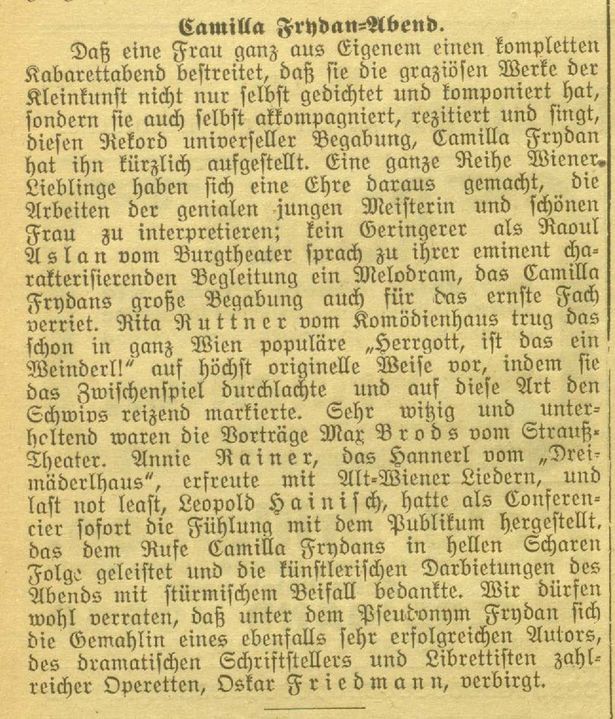

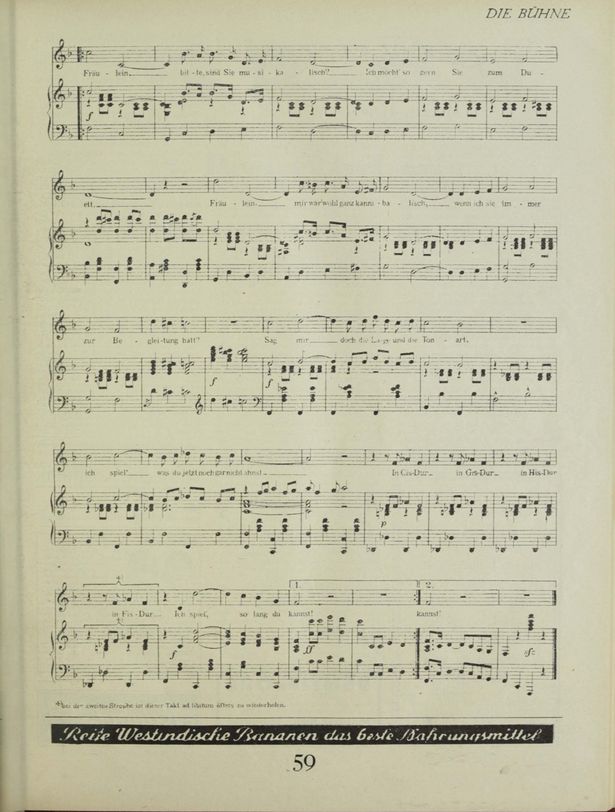

‘I need a girl who’s good and diligent, which is hugely important for the household. I need a girl who never sins and won’t quit her place every day’, goes the comically spirited refrain from the revue Die große Trommel (‘The Big Drum’). This piece was composed by Camilla Frydan, whom we have the pleasure of visiting today at the Frydan Publishing House in Berlin, which she founded just last year. You can sense this woman’s professionalism. She’s been demonstrating her musical prowess since her early childhood, through her upright and graceful posture at the piano, which she extends to her dedication towards the arts. She also possesses a humorous way of viewing the world. In her composition Ich brauch‘ein Mädel (‘I Need a Girl’) from 1925, for which Frydan also wrote the lyrics, she light-heartedly narrates the search for a young housekeeper from the perspective of a misogynistic, aging bachelor. In jest, she sketches the familiar, dependent relationship between an unpleasant, impractical gentleman and the young woman he needs to maintain his home. He insists that she work cleanly and live purely, as he wants nothing to do with filthy sins. Frydan’s hit playfully mocks this and cheerfully advocates for women’s independence. She exudes self-determination with every fibre of her being, demonstrating how free and bold the ‘modern woman’ can be.

g

Starting Early

Throughout her life, Frydan has been surrounded by artistic individuals who have found their passion, especially in music. Her brother is the librettist Ludwig Herzer, her sister Clothilde is a pianist, and her husband, Oscar Friedmann, is also a librettist and writer. In this creatively charged environment, the following was practically inevitable: at the end of 1901 Camilla began her piano lessons at the Conservatory of the Society of Friends of Music at the age of four. Just one year later, at the tender age of five, she gave her first concert, laying the foundation for her career as a child prodigy. She not only mastered the piano but also became a trained soubrette who composed her own songs accompanied by witty lyrics. Now, in her early forties, she is dedicated to new endeavours, most recently as the founder of her own music publishing house in her adopted home of Berlin. This new career step followed a successful tour of Germany. When asked which artistic areas she plans to explore further, Frydan responds with a smile.

g

The Role of Self

It is undisputed that Frydan’s biography has shaped her perspective on the world. The entire art industry is dominated by men, and in music as well as theatre are no exceptions. Frydan, as a soubrette, found her place in this field because it requires the delicate finesse of a female voice and a deep understanding of Commedia dell'arte, which demands a certain sensitivity. However, as a pianist, Frydan faced more challenges because there are few concert grand pianos where delicate female fingers are allowed to play. As a composer, Frydan had to fight for her place in her discipline from an early age and repeatedly had to assert herself. She has succeeded through her talent, determination, and chameleon-like adaptability, which, along with all her other artistic qualities, has also earned her the title of survivor.

‘I am particularly delighted that a woman has achieved this stage sensation! Finally, a woman has entered the ranks of the all-capable men! Bravo!’

n

Camilla Frydan, 1922

Camilla Frydan

born 3 June 1887, Wiener Neustadt

died 13 June 1949, New York

Biography

Camilla Frydan (née Herzl) was born on 3 June 1887, in Wiener Neustadt, the daughter of bank employee Heinrich Herzl (?–1919) and his wife Cäcilie (née Königsberger, (?–1928). Even as a child, she enthralled her family with her outstanding musical talent. However, she was not alone in possessing this gift, which blessed her entire family. Her older brother Ludwig (1872–1939) and older sister Clotilde (1873–1946) were also multi-talented musicians. During their formative years growing up together, the siblings influenced each other in a productive manner. In an era of growing demand for piano concerts, the ‘child prodigy’, as many called Camilla, left a lasting impression on the famous Ehrbarsaal concert hall in the heart of Vienna, filled with ‘an art-loving and elegant audience’.

In addition to her primary and high school education, she received private lessons in piano, music theory, harmony, and composition from her brother. Camilla’s skills soon outstripped her brother's teaching abilities. In 1901, she began receiving additional piano lessons at the conservatory from the esteemed pianist Wilhelm Rauch and private lessons from the English concert pianist John Charles Mynotti. At that time, her vocal instructor was the chamber singer Marianne Brandt (1842–1921).

g

Soon she became better known under her pseudonym Camilla Herzer. She managed to draw significant attention as one of the few women in the music field. Her reputation for consistently thrilling audiences whenever she performed as a pianist and singer earned her great recognition and marked her professional breakthrough. In 1907, she was under contract as a soubrette at the Raimund Theater, followed by engagements at the Neue Wiener Bühne and the Kabarett Fledermaus. There, she met Egon Friedell (1878–1938) and his fellow artists, including his brother Oscar Friedmann. Camille and Oscar married in 1910, and after their wedding, she began composing under the pseudonym Frydan. Their son Hans Henry was born the following year. Her artistic collaboration with her husband was also highly successful. Oscar Friedmann’s tragic death in November 1929 signified a complete reorientation in Frydan’s life. She moved to Berlin, where she created numerous revues for smaller theatres in the city. In 1937, she returned to Austria, as life for her as a Jewish person in Nazi Germany became perilous. After the Anschluss in 1938, Vienna also became life-threatening and, in 1939, Frydan managed to escape to Switzerland, where she stayed for a few months. From there, she obtained an entry visa to the United States. She lived in New York until her death on 13 June 1949, leaving behind approximately 500 individually composed musical pieces.

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

Source: ANNO/Austrian National Library

What remains?

k

Just two years after her return from Berlin to Vienna in 1937, Camilla Frydan was forced to flee from Nazi occupation in March 1939. Her brother-in-law, Egon Friedell, tragically fell from the window of his apartment a few days after the Anschluss, when SA men stormed in. In 1939, Camilla and her son managed to emigrate to Switzerland, where they lived for a year in Zurich. Frydan composed the symphony In the Dark of the Night during this period.

The death of her brother, Ludwig, ultimately led Frydan to emigrate to the United States. Together with her sister and her son Hans, she arrived in New York in November 1939. There, she not only founded Empress Music Publishing in 1945 but also published several of her own compositions. She quickly gained popularity in New York, with around 500 individual pieces attributed to her. Frydan found success not only as a composer but also as an entrepreneur in the music industry. She continued working as a publisher in New York until her death in 1949.

Despite her new and successful life in the USA, the past in Vienna was not easily forgotten, leading to a struggle over the inheritance of her brother-in-law, Egon Friedell. Hans Henry, Camilla’s son, was considered the rightful heir.

. He was a film actor and had covered the costs of his uncle Egon’s and grandmother Caroline Trisch’s funerals. After 1945, it proved challenging to have him recognized as the lawful heir to the estate. Numerous documents and letters in correspondence between New York and Vienna in Camilla Frydan’s estate shed light on this issue and indicate that the estate was stolen by Egon Friedell’s former housekeeper, Frau Kotab, along with her mother and her husband Franz. In one letter, Camilla Frydan describes the three as ‘fanatical National Socialists’. The ongoing struggle for the inheritance, as preserved in the correspondence, illustrates how any sense of justice in Austria had been lost after 1945, and how perpetrators like the Kotabs remained untouched by the judiciary for a long time.

g